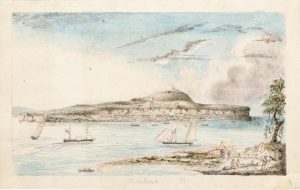

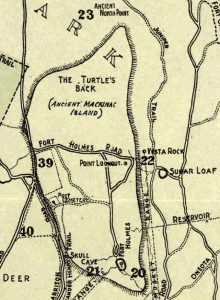

Approaching Mackinac Island by boat offers excellent insight of ancient geological forces which shaped the landscape we enjoy today. As the last glaciers retreated about 11,000 years ago, a tremendous amount of meltwater filled ancient Lake Algonquin to a depth of about 220 feet higher than current Lake Huron. At that time, only the highest point of Mackinac Island stood above the water, being about ½ mile long and nearly ¼ mile wide. For many generations, Native Americans have referred to this high point as the Turtle’s Back, as its domed shape creates the perception of a giant turtle floating on the water.

For about 3,000 years, the churning waves of Lake Algonquin eroded softer portions of limestone along the shores of this ancient island. As softer sections were removed, harder portions of recemented limestone, known as Mackinac breccia, were left behind, creating features which are still visible today. The two most prominent of these are among Mackinac’s oldest natural wonders – Skull Cave and Sugar Loaf.

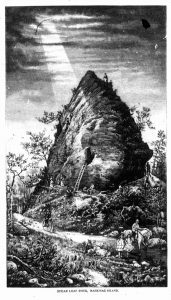

Both of these formations are examples of sea stacks which resisted the erosive power of Lake Algonquin waves. These pillars of breccia became separated from the ancient island as softer rock was gradually washed away. Both features also include caves, which were slowly excavated by the pounding surf, thousands of years ago.

Start your tour of the Turtle’s Back by heading north from Fort Mackinac, along Garrison Road and Rifle Range Trail. Upon your approach, high bluffs of the ancient island rise before you, with reconstructed Fort Holmes perched at the top. Skull Cave is located near the southwestern corner of the ancient island. At first, it may be difficult to imagine this formation as a sea stack, as it is smaller and more eroded than Sugar Loaf. The cave itself largely collapsed by 1850, and was subsequently filled in further. Like other formations across Mackinac Island, this cave was used as a sacred gathering place by nearby Anishinaabek residents, who interred their dead here for centuries. As a measure of respect, and to help preserve this ancient formation, access beyond the fence is not permitted.

Published on August 19, 1842, an article in the Sandusky Clarion, of Sandusky, Ohio, included the following description of Skull Cave. “Not far from Fort Holmes is a small cave, called Skull Cave Rock, because the Indians were in the habit of interring the dead here. The passage in is necessarily on the hands and knees. The cave itself is about twelve feet square… The rock is light colored limestone, and is constantly crumbling away. The little stone that breaks off from the main rock have many holes in them, and are very easily reduced to a powder.”

As you leave the cave, continue along Garrison Road, towards the cemeteries. Here, the high bluff of the ancient island largely remains hidden by trees. Venture past the Protestant Cemetery and turn right on Fort Holmes Road, winding your way up a hill to the high promontory known as Point Lookout. From here, a grand vista opens below you, foremost being the 75-foot pyramid of Mackinac breccia known as Sugar Loaf.

During her visit in 1852, Juliette Starr Dana climbed a ladder which once allowed tourists to enter a small cave in the side of Sugar Loaf, about 15 feet above the ground. Crouching down and examining its surface, she wrote, “It seemed water-worn & the whole rock within & without was full of strange little holes, with the insides nicely polished as by the action of water.” Today, safety concerns prohibit climbing the formation or entering the cave, but a tour around its base is well worth the journey.

In 1945, geologist George M. Stanley noted that Sugar Loaf stands about 300 feet east of the ancient island, and the top of this formation was a small island of its own. He wrote, “It is a magnificent display of limestone breccia. One may see by close inspection, fragments of bedding limestone of various sizes from vary small fragments to blocks several feet long, tilted in random directions and all cemented into a solid mass.”

Leaving Point Lookout, continue down the road to Fort Holmes, located at the southern exposure of ancient Mackinac Island. The renowned geologist Frank B. Taylor visited this spot in 1890 and 1891. During the period of Lake Algonquin high water, he noted that we “would stand alone in a wide expanse of water. The nearest mainland would then be about 30 miles to the south and the nearest islands about 20 miles to the north and southwest. In all other directions open water would stretch away 100 to 200 miles.”

In more modern times, this grand view of the Straits of Mackinac has been celebrated time and again by visitors for the last several centuries. In 1836, theologian Chauncey Colton exclaimed, “I may venture to assert that there are few scenes in nature which are equal to the view from Fort Holmes… To the west, the eye follows the straits until it rests on the bluffs at the northern extremity of Lake Michigan, or is lost in its transparent waters; while all around stretches the vast expanse, with here and there an island, looking pure and peaceful as if the impress of sin had never been laid upon it.”