“If there ever was an epic of peril and of rescue this was one.” – Robert Graves, 1891

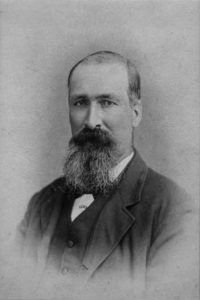

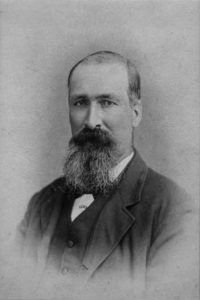

Ice persisted in the Straits of Mackinac on April 15, 1883. In spite of blustery conditions, Thomas Marshall, keeper of the Spectacle Reef Light Station, departed Mackinac Island in a small sailboat, accompanied by three assistants; his son James, Edward Chambers, and Edward Lasley. All three families had deep ties to the Mackinac Island community, many of which persist today. Their small vessel never reached the remote lighthouse and one of their unlucky crew would not survive the fateful journey.

Located 23 miles southeast of Mackinac Island, Spectacle Reef Light opened in 1874 to mark treacherous shoals near the entrance of Lake Huron. Situated 10 miles from the nearest point of land, the outpost is exposed to extreme elements of wind, ice, and surf for many months of the year. Several other shoal lights exist in the straits region, including the Waugoshance Lighthouse, near Wilderness State Park and the headwaters of Lake Michigan.

In a widely printed newspaper article, written June 15, 1891, special correspondent Robert Graves recounted the day in vivid detail: “The weather was bitter cold, a gale was blowing and the lake was full of ice, both fixed and floating… Suddenly a gust of wind and an accident to the rigging overturned the little vessel, and the men were thrown into the icy water. All contrived to get hold of the gunwale, and by an almost superhuman effort Chambers cut away the foremast with a pocket knife, but this did not help matters much. Young Marshall suffered the most, being under water more than the others, and the keeper in time was greatly exhausted by the constant hold he kept on his son…”

Remarkably, the four men survived icy waters for three hours, clinging to their overturned craft. As they drifted towards Bois Blanc Island, their cries for help were finally heard by lighthouse keeper Lorenzo Holden and fishermen brothers, Alfred and Joseph Cadreau. The above account continues, “Gallant young Joseph Cardian [Cadreau] at once undertook the rescue in a small skiff. His companions told him he was only going to his death, as a formidable array of breakers, thick with ice, was crashing upon the shore, with a rough sea beyond.

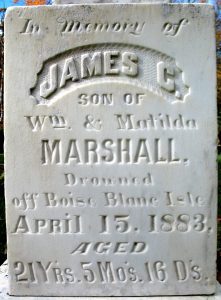

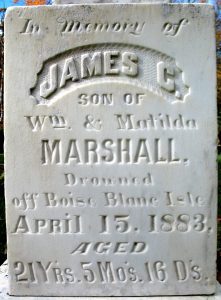

The young man knew no such word as fail, and though often all but swamped finally managed to force his frail craft out to the wreck. Young Marshall was by this time almost dead, and Chambers and Lasley–the latter suffering terribly from an injury to one of his legs–nobly insisted that the keeper should take the first chance and with his son endeavor to reach the shore. Young Marshall feared the skiff would not hold two, and begged his father to go first. ‘Go, father,’ said he; ‘don’t mind me.’ These were the brave boy’s last words. He was dragged into the boat by his father and Cadreau, where he lay still. As the skiff neared the shore it was capsized in the breakers.” Tragically, young James Marshall sank beneath the icy waves.

Nearly frozen, William Marshall was coaxed from the brink of death by the Holden family, who covered him with blankets and rubbed his body for five hours to restore circulation. The body of James Marshall, age 21, was later recovered from 24 feet of water and was buried in Mackinac Island’s Ste. Anne’s Catholic Cemetery.

On June 7, 1883, Joseph and Alfred Cadreau were awarded gold lifesaving medals for their heroism. Established by an Act of Congress in 1874, the award is now one of the oldest medals granted in the United States. The following year, on July 15, 1884, an award ceremony was held on Mackinac Island to honor the two brothers. A special dispatch to the Detroit Free Press noted, “The Reward of Heroism: The first-class gold medals were presented to Joseph and Alfred Cadrau (sic) yesterday by Commander F.A. Cook, of the United States Navy, on behalf of the United States. It was a gala day for Mackinac, the town being crowded with people from the surrounding country.” In subsequent years, both brothers spent some time working for the U.S. Lighthouse Service. In 1889, Alfred married Therese Bennett, daughter of Charles and Angelique Bennett, who lived at Mill Creek for many years.

Nearly every person in this story can be part of your next trip to the Stratis of Mackinac. Learn all about the Marshall family by visiting the Old Mackinac Point Lighthouse and Straits of Mackinac Shipwreck Museum. On Mackinac Island, you can pay respects to the Marshall, Lasley, Chambers, Cadreau, and Holden families at the Ste. Anne’s Catholic Cemetery and Protestant Cemetery along Garrison Road, near Fort Holmes.