As “all roads lead to Rome,” so in this island world all carriage drives and by-paths seem to lead, infallibly to Sugar Loaf … What unthinkable convulsion of Nature dropped it there, as if from the sky? J.M. Robinson (1912)

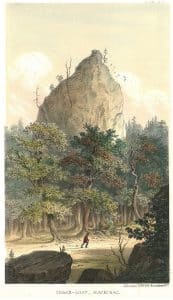

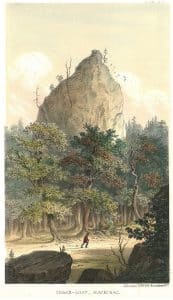

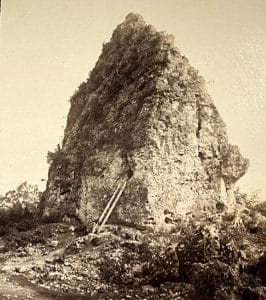

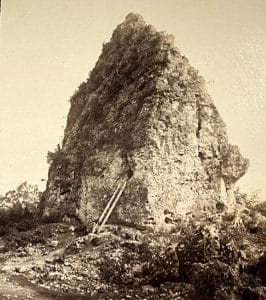

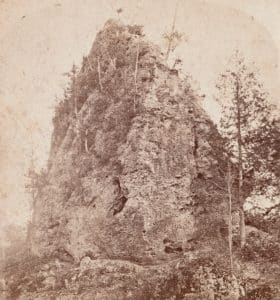

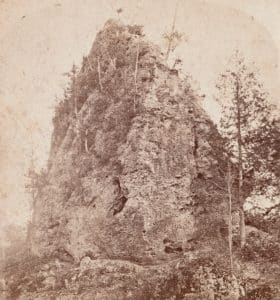

Sugar Loaf and Skull Cave are two of Mackinac Island’s most famous curiosities. In geological terms, both formations are sea stacks, once attached to tall cliffs of ancient Mackinac Island. About 11,000 years ago, deep postglacial lakes eroded softer limestone, leaving behind tall stacks of Mackinac breccia, a type of durable recemented limestone. Today, Sugar Loaf rises about 75 feet above the forest floor and sits about 300 feet from the cliff called Point Lookout.

Caverns were also formed within each stack as limestone deposits disintegrated. Resembling an inverted keyhole, the cave in Sugar Loaf pierces its north face, about eight feet above the ground. It’s actually the entrance to a fissure which penetrates the formation, widening to a small room before exiting through a tiny opening on the southern side.

Visitor Accounts

Over the past two centuries, Sugar Loaf has been visited by many thousands of visitors from across the globe. For much of the 19th century, access to its cave was provided for guests by a wooden ladder. On June 26, 1845, a writer for the Boston Post noted, “There is quite a large cave … reached by means of a ladder. It will accommodate some six or eight at a time, and is high enough for the tallest to stand erect. Here ladies and gentlemen sometimes take their lunch, and gentlemen alone smoke their cigars.”

Leaving A Mark

In the mid-19th century, overzealous guests unfortunately left their mark on Mackinac’s natural features. Juliette Starr Dana entered Sugar Loaf’s cave on July 29, 1852. She recalled, “There was a level platform at the mouth where we could stand upright, but we were obliged to stoop to enter. Again we could stand up, but the sides & top were very ragged & the edges projected so sharply that we were obliged to move with caution. Here we found a great many names written upon the almost white projections of the rock. It seemed water-worn & the whole rock within & without was full of strange little holes, with the insides nicely polished as by the action of water.”

Eugene Cyrus Dana (a distant relation) visited Sugar Loaf in August 1874. He noted, “The American Vandal” had been here too, and the walls of the cavity had people’s names carved on them and visiting cards strewed the floor. Of course we added ours to the collection.”

When Mackinac National Park was established in 1875 protecting the island’s natural wonders became an important (if frustrating) priority. In 1882, Mackinac’s most self-promoting officer, Lieutenant Dwight Kelton, published Annals of Fort Mackinac, an early guidebook to the National Park. Just two years later, he was accused of defacing government property. Kelton had decided to cut “stunted trees,” bushes, and roots protruding from the surface of Sugar Loaf. Defending his actions to Captain George Brady, he explained, “Of course the appearance of the rock has changed it now stands out boldly against the sky, and being isolated from the tall surrounding trees, it can be seen in all its majesty.” While the text of his book called the site Sugar Loaf, his map featured a new name for the formation, “Kelton’s Pyramid.”

Eager for mementoes, visitors of this era peeled bark off birch trees, carved cedar walking sticks, and broke pieces of limestone from geological formations. In August 1894, Captain Clarence Bennett threatened to expel visitors from the park if they were found guilty of defacing Sugar Loaf. Less than a year later, however, the U.S. government transferred the national park to the State of Michigan. In 1895, the newly formed Mackinac Island State Park Commission accepted responsibility for protecting the island’s natural wonders.

Mackinac Island saw several improvements for guests near the turn of the 20th century. Automobiles were banned in 1898, a Deer Park was established in 1901, and Lake Shore Boulevard (M-185) was completed in 1904, encircling the island’s shoreline. About 1900, a sturdy wooden staircase replaced the rickety ladder to Sugar Loaf’s cave, remaining in use for two decades.

Today, climbing Sugar Loaf is not allowed, both for visitor safety and to preserve this iconic limestone formation. While Mackinac’s breccia is durable, erosion still occurs, due to both natural and human factors. The last two images, of Sugar Loaf’s northern face, were taken about 130 years apart. The large protrusion on the right side of the 1890s photo fell off completely sometime in the latter half of the 20th century. If treated with care, this dramatic natural wonder will awe visitors for centuries to come, deep in the woods of Mackinac Island.