On November 22, 1822, the Detroit Gazette reprinted a remarkable tale that captivated readers across the country. The story originated in New Orleans and first appeared in the Louisiana Advertiser that September. Dozens of newspapers in at least 16 states—and in the nation’s capital—eventually printed the account. The tale began eight years earlier, during the Battle of Mackinac Island.

A short version from the November 13, 1822, edition of the Gettysburg Compiler reads: “Something Extraordinary. On the 15th of August at New Orleans, a musket ball was extracted from the body of Mr. J. Wingard, where it had remained since the 4th of August, 1814; when it was received at the battle of Mackinac, under Col. Croghan. When extricated, the part flattened by the bone was covered with a black crust, which on being dried and set fire to, exploded with a white flame similar to fresh powder, with the exception of a sulphurous [sic.] smell, from which it was entirely free.”

Reading this improbable tale prompts many questions. Who was J. Wingard? Did he truly carry a musket ball—and powder—inside his body for eight years, traveling from Mackinac Island to New Orleans? How did this injury occur, and what became of him? A closer look offers answers to this forgotten soldier’s sacrifice.

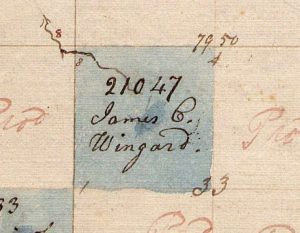

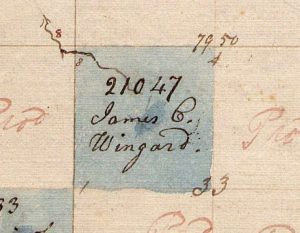

Sergeant James C. Wingard

British forces captured Fort Mackinac during a surprise attack on July 17, 1812. American forces suffered additional losses, including the surrender of Detroit the following August. In January 1813, the Battle of the River Raisin near Monroe, Michigan, ended in a bloody and decisive British victory. The defeat devastated the Kentucky Volunteer Militia and the 17th U.S. Infantry and inspired the rallying cry, “Remember the Raisin!”

When news of these defeats reached Kentucky, 4,000 Kentuckians volunteered to fight. On May 11, 1813, James C. Wingard enlisted as a sergeant in the 1st Company of the 17th Regiment of U.S. Infantry. At enlistment, he was a 34-year-old carpenter. Born in Maryland around 1779, Wingard stood 5’11” tall, with gray eyes, dark hair, and a fair complexion.

Lieutenant Colonel George Croghan led the American attack on Mackinac Island. Croghan Water Marsh later took his name.

With fresh Kentucky reinforcements, American forces achieved victories in late 1813, including the recapture of Detroit. By the following summer, they prepared to retake Mackinac. A letter from Detroit dated July 3, 1814, reported: “The expedition against Mackinaw will set out the first fair wind up the river; the whole commanded by the brave colonel G. Croghan and major Holmes. Their command will consist of about seven hundred men…They calculate on serious business, before we get possession of the place.”

Headwinds delayed the expedition, but all five American gunships entered Lake Huron by July 13. To join them, Sergeant Wingard and other foot soldiers marched from Detroit to Fort Gratiot at Port Huron. One expedition member wrote: “The land forces arrived here yesterday, having marched by land fifteen miles through a very ugly and wet country without even a path the greater part of the way.” After boarding the ships, the flotilla began its fateful journey north.

The Battle of Mackinac Island

After the War

Despite his serious wound, Wingard continued his service. In October 1814, he received a furlough in Cincinnati, Ohio, and records noted he was “debilitated by a wound.” Sergeant James Wingard received his discharge at Newport, Kentucky, on May 6, 1815. He and his wife Elizabeth then settled in Hamilton County, Ohio.

After the war, Wingard received an invalid pension authorized for wounded veterans. Initially, only injured commissioned and non-commissioned officers and heirs of fallen soldiers qualified. The U.S. Congress placed Wingard on the pension roll on April 16, 1816, with an annual allowance of $30. Two increases followed, and he eventually received $96 per year for his Mackinac Island injury.

Congress also authorized land grants for War of 1812 veterans. The first military bounty lands lay in Arkansas, Illinois, and Missouri. Wingard applied on March 27, 1819, for a 160-acre tract in northern Arkansas Territory. He received his grant on January 28, 1822.

A Beautiful White Blaze

On August 15, 1822, surgeons in New Orleans placed James Wingard on an operating table. Previous attempts to remove the musket ball lodged in his pelvic bone had failed. When surgeons finally extracted it, they observed a mysterious dark crust on the flattened surface. After drying the substance, they scraped some onto a glass plate. The longer published account concludes: “a part of which…was put on a strip of white paper, the end of which was set on fire, and no sooner had the fire come in contact with the supposed powder than it exploded with a beautiful white blaze, much to the consternation of all the gentlemen present: a second trial was made with equal success.”

The story, however, omits the most tragic detail: Wingard died that day at 43 years of age. His pension record simply states, “Died the 15th August 1822. Original Certificate of Pension surrendered.”

Two hundred years ago, newspapers across the country marveled at the incredible tale of Sergeant James Wingard, a survivor of Mackinac Island’s most terrible day. As families gather this Thanksgiving, may we give thanks for all veterans, including those whose stories fade with time. Their courage and sacrifice preserve the freedoms we enjoy—and too often take for granted.