When British soldiers began constructing the fort in late 1779, they planned from the outset to mount multiple artillery platforms. British troops hauled their guns up from the old mainland post at Michilimackinac to arm the new fort on the island. By 1780, Fort Mackinac’s artillery included two mobile bronze 6-pound field pieces, two heavy iron 6-pound guns mounted on stationary garrison carriages, four small bronze amuzetts, two wall guns, and a 4¼-inch bronze mortar. By the end of British occupation in 1796, the arsenal had expanded to include two small iron howitzers and eight iron ½-pound swivel guns. Soldiers distributed these weapons around the fort to provide both point defense and long-range fire. When British forces turned the fort over to the United States in September 1796, they removed all of their artillery.

When the War of 1812 began, American forces defended Mackinac with two bronze 5½-inch howitzers, two bronze 6-pound garrison guns, one bronze 3-pound garrison gun, and two iron 9-pound garrison guns. This small battery failed to prevent the British from recapturing the fort on July 17, 1812. After taking control, British troops discovered that some of the guns had originally been captured from British forces at Saratoga in 1777 and Yorktown in 1781. The British quickly strengthened the fort’s defenses, and by the end of the war they maintained nearly 25 artillery pieces at Mackinac.

After the war ended in 1815, American troops returned to Fort Mackinac and once again had to mount new artillery, as the British had removed their guns during the evacuation. In the years that followed, the U.S. Army added and removed artillery depending on perceived threats and strategic needs. When Colonel George Croghan inspected the post in 1842, he ordered most of the guns shipped to Detroit. Since infantry units then garrisoned the fort, Croghan concluded that “an infantry garrison wants not a full battery.”

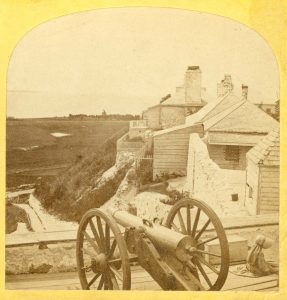

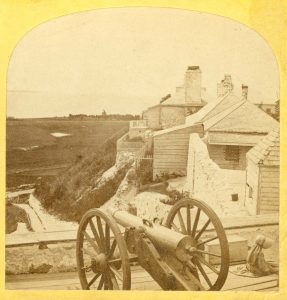

Despite this assessment, artillery units did occasionally serve at Fort Mackinac. In 1852, Battery L of the 4th Artillery Regiment arrived at the post, likely equipped with bronze 6- and 12-pound field guns. The soldiers built a floating target and used the Straits of Mackinac as a firing range, though they had to drag their guns up and down the hill from the fort for each drill. Artillerymen from the 2nd Artillery Regiment continued to serve at Mackinac until the outbreak of the Civil War, when Captain Henry Pratt and Battery G received orders to report to Washington, D.C.

After the Civil War, Fort Mackinac lost nearly all of its military importance. In 1875, the Army designated the post as the headquarters of Mackinac National Park and supplied a small collection of obsolete artillery pieces for ceremonial use. These included two bronze 6-pound guns, two bronze 12-pound guns, a 12-pound howitzer, and a massive 10-inch siege mortar. Soldiers fired these weapons with blank charges to mark special occasions, including the arrival of the first ship each spring, George Washington’s birthday in February, the deaths of prominent generals and former presidents, and the Fourth of July.

On a daily basis, members of the guard detachment fired a single gun at reveille and retreat. In 1887, the cost-conscious War Department refused to fund additional ceremonial firings, and the guns of Fort Mackinac fell silent. The St. Ignace News remarked that “People passing near the fort in the evening, feel rather disappointed after they have humped themselves up into a ball and got ready for a shock to find that the cannon will not be fired any more. Nervous people will be glad; and people without clocks will be sorry to hear of this change.” Much to the disappointment of the “nervous people,” the War Department restored funding for ceremonial firings in late 1888.

When the last soldiers departed the fort, the War Department removed all remaining artillery pieces. At the request of the Mackinac Island State Park Commission, the federal government supplied additional obsolete guns in 1905 to rearm the fort, now a historic site within Mackinac Island State Park. These weapons remained on display until the early 1940s, when officials destroyed them as part of a World War II scrap drive. Today, two reproduction 6-pound cannons stand guard on the gun platforms and serve in interpretive demonstrations. The only original artillery piece at Fort Mackinac is the “Perry cannon,” an iron 12-pound gun that served aboard the American fleet that attempted to recapture Mackinac Island during the War of 1812. Visitors can see it on display in the Island Famous in These Regions exhibit.