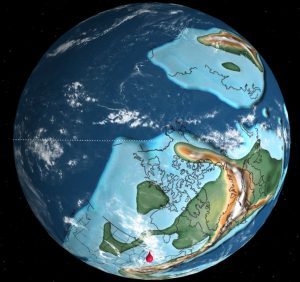

Long before earth’s modern continents developed, lower Michigan was shaped like a large basin, located south of the equator. A series of warm, shallow seas gradually filled this area then evaporated, leaving sediments behind. This process repeated itself many times over millions of years, eventually forming thick layers of limestone.

Shelled marine life flourished in these salty, tropical seas. After these animals died, their calcium-rich remains sank to the sea floor, sometimes becoming fossilized. Today, dozens of fossil types are found at the Straits of Mackinac, including corals, brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, bivalves, and trilobites.

Describing the process in 1957, Michigan geologist Helen Martin wrote, “On this [sea] floor lime muds were deposited and as the animals died their shells fell into the muds which then became the fossil cemeteries of the life of the sea. You can see what sort of rock was made from these muds along Highway 31 just south of Mackinaw City and in the bed of a little stream – Mill Creek.”

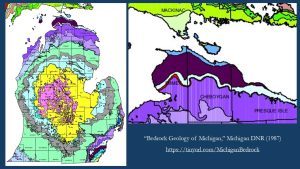

Over millions of years, the Michigan Basin slowly filled in like a set of nesting bowls, with new layers deposited on top of older ones. Today, layers of rock which are exposed at the Straits of Mackinac are buried about 6,000 feet below the surface in central lower Michigan. Even further south, the Bois Blanc Formation outcrops again in southeast Michigan, western New York, and southeast Ontario.

The Age of Fishes

In addition to abundant shelled invertebrates, the Devonian Period is noted for an amazing diversity of fish species. Known as the “Age of Fishes,” this period featured placoderms with armored head plates, the first sharks, lobe-finned fish (including lungfish), and acanthodians (fin-spined fish).

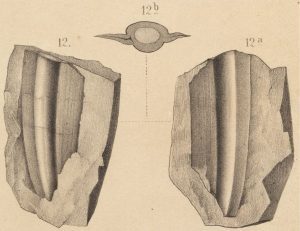

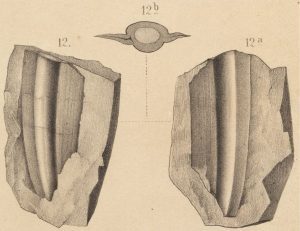

Now extinct, acanthodians were the first fish to evolve jaws and scales. Nicknamed “spiny sharks,” fish in this group had bony spines along the front edge of each fin. Rigid spines may have prevented them from sinking into the mud while resting on the sea floor. Their full body form is unknown as it was largely composed of cartilage which decayed before being fossilized. In the Great Lakes region, fossilized spines have been found in Ohio, Ontario, New York, and extreme southeastern Michigan. In northern Michigan, a few specimens have been recovered from abandoned rock quarries in layers of Middle Devonian limestone.

Machaeracanthus at Mackinac

The earliest account of fossils at the Straits of Mackinac dates to 1817, when fossilized shells were collected on Mackinac Island. To date, this Machaeracanthus spine is the first known vertebrate fossil to be found at the straits. This specimen also appears to be the first of its kind from Michigan’s Bois Blanc Formation. In 2018, Jack Stack and Lauren Sallan published a comprehensive study of the state’s Devonian fishes. They described Machaeracanthus from several Middle Devonian deposits, including the abandoned Kelly Island Limestone Quarry at Rockport State Park, in Alpena County, and from the Onaway Stone Quarry in Presque Isle County. Dr. Friedman noted the U-M Museum of Paleontology has one very small spine fragment from the Bois Blanc Formation, but from the northeast shore of Lake Erie in Ontario.

Invitation to Explore

As you visit the Straits of Mackinac this summer, remember wonders come in all shapes and sizes. While you’re here, be sure to enjoy the grandeur of Arch Rock, towering trees, soaring eagles, and the vast expanse of Lake Huron’s crystal waters. You’re also invited to slow down (sit down, even) and ponder the earth beneath your feet. You may discover blooming wildflowers, salamanders in the dirt, or delicate butterflies with gossamer wings. If you’re lucky, you may even reveal evidence of ancient life which thrived in very different waters, nearly 400 million years ago.