Christmas in the United States is a federal holiday and arguably the most widely celebrated holiday in the nation. Americans devote more retail spending and holiday decorations to Christmas than to any other holiday during the year. Despite its prominence today, Americans have not always celebrated Christmas universally. In fact, many traditions now associated with Christmas in the United States developed far more recently than most people realize. Most modern American Christmas customs emerged during the Victorian era of the 19th century.

This period also marked the height of Fort Mackinac’s use as an active military garrison. As a result, the history of Christmas traditions at the fort closely reflects broader national trends and the experiences of local residents.

From the earliest days of European American history, Christmas traditions varied widely. Different European cultural groups celebrated the holiday according to their own customs and within specific geographic regions. These traditions rarely blended with one another at first. In New England, for example, communities with strong Puritan roots largely avoided Christmas celebrations. Puritans viewed the holiday as a remnant of what they considered the corrupted practices of the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church. In contrast, Southern colonies embraced Christmas more fully. Their celebrations reflected English royalist traditions and often lasted for several days.

As the United States developed a stronger national identity during the 19th century, Christmas traditions began to follow a shared national trajectory. This shift occurred alongside increasing cultural diversity driven by immigration and population growth through westward expansion and urbanization. At the same time, Americans grew increasingly concerned about regional sectionalism. These forces created a longing for imagined simpler times and a desire for shared national traditions. Together, they shaped the evolution of Christmas in America.

Elizabeth T. Baird recalled celebrating Christmas as a young girl on Mackinac Island as early as 1823. She remembered familiar traditions that included a large meal, prayer, and singing with family.

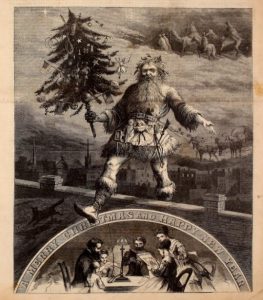

By the early 19th century and throughout the Victorian era, many Christmas customs familiar to Americans today had begun to take shape. Families exchanged Christmas cards and decorated evergreen trees inside their homes. Communities sang Christmas carols in public spaces. People prepared large meals to host gatherings of family and friends on both Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. During this period, Americans also developed their own version of Santa Claus. Clement Moore introduced the character in his 1822 poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas.” The first documented storefront Santa impersonator appeared in Philadelphia in 1849.

Christmas traditions even crossed sectional boundaries during the American Civil War. Both Union and Confederate soldiers observed the holiday in various ways. National publications such as Godey’s Lady’s Book and Harper’s Weeklyplayed a major role in shaping public perceptions of Christmas. These publications helped define a shared American Christmas identity that endured from the mid to late 19th century.

Horse-drawn carts like these transported food from the mainland to supply holiday meals for Mackinac Island residents.

Mackinac Island reflected these national trends on a smaller scale among both civilian and military communities. Islanders consistently emphasized the importance of a large Christmas dinner, even during the isolation of winter months. In 1823, Elizabeth Baird recalled a Christmas meal that included roast pig, roast goose, chicken pie, round beef, sausage, headcheese, fruit preserves, and cake. After the meal, families gathered for prayer, singing, and gift-giving.

Similar traditions appeared decades later at Fort Mackinac. An 1883 military commissary order listed chicken, duck, and turkey for holiday meals. Troops shipped these supplies by rail to Mackinaw City and then transported them across the frozen straits by horse-drawn cart. Harold Dunbar Corbusier, the son of an Army surgeon stationed at Fort Mackinac from 1883 to 1884, described nearly identical customs. In his journal entry dated December 25, 1883, he wrote, “We had a Christmas tree this morning. … I received the ‘Theatre Royal,’ a knife, the Calendar of American History and several other little presents.” His account mirrors traditions still familiar to Americans in the early 21st century.

Corbusier recalled celebrating Christmas and New Year’s at Fort Mackinac in 1883–84 with an indoor Christmas tree, gift-giving, and meals shared with family and friends.

As the end of 2025 approaches and the New Year of 2026 nears, this history offers an opportunity for reflection. The present does not exist in isolation from the past. Instead, past events and traditions shape modern life in meaningful ways. The Christmas and New Year celebrations of earlier generations on Mackinac Island remind us of this continuity. They reveal how American Christmas traditions grew from a distinctly American past and continue to connect people today through shared celebrations of family, friendship, and life.

A Song For New Year’s Eve:

The fire-light glows upon the hearth;

Come, gather round, kind friends!

To-night the New Year has its birth,

To-night the Old Year ends

So fill your glasses to your rim,

An let us say farewell to him!

(Excerpt from “A Song For New-Year’s Eve,” Harper’s Weekly 5 Jan. 1867)

Additional Christmas reading: