Across Great Britain, its expanding empire, and the American colonies, voting rights remained highly restricted. In general, only white men over age 21 who owned taxable property could vote. With few exceptions, women, Native Americans, free and enslaved Black people, and the poor could not vote. Catholics were also usually denied the franchise. Election practices and schedules differed between Britain and the American colonies.

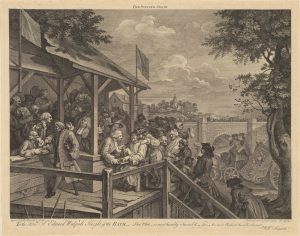

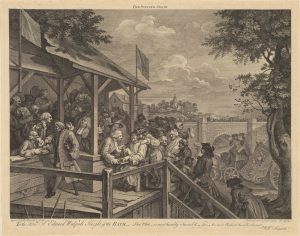

Despite these limits, British subjects at home and abroad understood their civil rights and worked to defend them. These concerns became especially strong when elections involved the British army. Many Britons distrusted the standing army and viewed it as a possible tool of tyranny. As a result, authorities usually removed troops from polling places on election days. In Britain and the colonies, officials often sent soldiers out of towns entirely. Practical concerns also shaped these decisions. Voters frequently cast ballots at roadside inns. Since troops often lodged there, officials moved soldiers elsewhere to make room for voters.

Stationing troops near polling places could quickly spark accusations of voter intimidation, especially in the colonies. In 1768, General Thomas Gage confined New York City troops to their barracks during an election. He also forbade them from having “any intercourse with the inhabitants” that day. In Boston the following year, commanders again restricted troops to their barracks during the May 1769 election. Despite this, voters protested. They asked military authorities to remove troops entirely so they could enjoy “the full enjoyment of their rights.” When the officer refused, colonial leaders accused “armed men” of interfering in the election. [1]

Quebec, which included Michilimackinac after the Quebec Act of 1774, had no elected legislature. Instead, a royal council of civil, military, and church officials governed alongside the governor. Even so, residents of Michilimackinac remained politically engaged. They followed colonial and British politics, including parliamentary elections overseas. Newspapers and letters, often months old, carried news from Britain and the Atlantic colonies.

The political world surrounding Michilimackinac in the late 18th century was complex and changing. It blended British traditions with French Canadian legal and political customs. Many of these ideas later shaped the political framework of the United States. Although elections likely never occurred here, politics influenced daily life at Michilimackinac. Ask about 18th-century politics during your next visit to Colonial Michilimackinac. Consider joining Mackinac Associates, whose support makes many programs and exhibits possible.

[1] John McCurdy, Quarters: The Accommodation of the British Army and the Coming of the American Revolution, (Cornell University Press, 2019), 171, 185-86